One suggestion that seemed particularly relevant this week

was Twelve Kvetchy Men. Not because we’ve probably been

spending a lot of time with family (and our own, lovable kvetchy men) but

because this week’s Torah portion rounds out the story of exactly 12 kvetchy

men: Joseph and his 11 brothers. Kvetchy is an understatement, though. Over the course of their story, we have

learned that these 12 brothers can be rash, jealous, deceptive and unforgiving. They take up many pages of Genesis in a

long saga of vicious behavior…culminating in them plotting to kill their

brother Joseph. Only after this

terrible episode and then years of maturation, the brothers are finally able to

reconcile.

They live together peacefully, we think, in Egypt for about

17 years until their father Jacob grows ill and lies on his deathbed. The brothers gather around to hear

Jacob’s final speech. It’s quite a moment. Imagine them huddled close. Think of how far they have come from

flinging Joseph deep into a pit to die to now standing side by side in brotherly

solidarity. As one group they go

to bury Jacob, giving him his last honor.

But then a curious thing happens on the way back from

burying Jacob. After those 17

years of solidarity and brotherly love, Torah says, “Now

Joseph's brothers saw that their father had died, and they said, "Perhaps

Joseph will hate us and return to us all the evil that we did to

him." The brothers send an

intermediary to remind Joseph that Jacob commanded that he forgive his brothers

for what they did all those years ago.

The problem? Torah has no

record that Jacob ever said that.

Are the brothers back to their old

tricks? Was there never really a

peace between them?

The rabbis take this up this problem

in the midrash[1]. They ask: What did the brothers see after the funeral

that frightened them so much? The

rabbis answer: As they were returning from the burial of their father, the

brothers saw Joseph go to the pit into which they had hurled him, in order to

bless it. He blessed the pit with

the benediction: “Blessed be the place where God performed a miracle for me,”

just as any man is required to pronounce a blessing at the place where a

miracle had been performed on his behalf.

[The brothers stood off at a distance, though, and did not hear the

blessing.] When they beheld him at the pit, they cried out: “Now that our

father is dead, Joseph will hate us and will fully requite us for all the evil

which we did unto him.”

One misinterpreted action is enough for the brothers to

question years of living peacefully together.

The uncertainty leads the brothers to do two things. First, they do not approach Joseph

directly – they speak to him through an intermediary. Second, they lie – putting words into Jacob’s mouth. But the rabbis ask: can we really blame

them? They teach: “[the brothers’] statement is introduced to teach us the

importance of peace. The Holy One,

Blessed be God, wrote these words in the Torah for the sake of peace alone.”

It is almost as if the rabbis are saying “the ends justify

the means.” Sometimes moving on,

or simply finding a productive way forward is much more important.

At the end of 2012, there are many complicated feelings

still in the air. In some respects

it was an inspiring year. The Olympics brought the world together; the Giants

won the Superbowl. It was also a

very difficult year, with many issues still unresolved. Civil war in Syria, the looming “fiscal

cliff,” rebuilding after the hurricane, and the debate around gun control

gearing up as we still mourn Newtown. Not to mention all the things we have

each experienced personally.

We’re going into 2013 with this complicated desire to just

shake off the difficult parts of 2012 but also with the aspiration to address

these most pressing needs in our personal lives and in our local and global

communities.

This week, Torah speaks to this uncertainty and our

conflicted feelings. It asks the best way to move forward when the pain and

mistrust runs deep. We could read

the midrash to say that we should bluff our way into 2013, doing whatever

necessary in the name of resolution, but I think there is more than that.

It teaches the importance of compromising. It encourages us

to seek help when we cannot find the words or the courage to face the conflict

in our lives. It tells us that the path to peace is not a straightforward one.

That even when we think we have found resolution, there is still the natural

potential for self-doubt or backsteps.

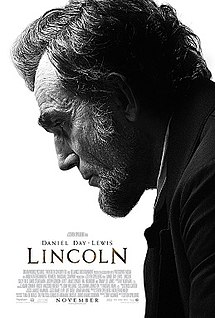

To go back to the #IfTheMovieWasJewish meme, Mark and I

recently saw the movie Lincoln. Given this week’s Torah portion, one

part felt very Jewish. President Lincoln is speaking to Thaddeus Stevens, a man

with very noble aims. Stevens’ feelings: your principles should drive you

forward, no matter what. Lincoln

counters with a more practical but powerful metaphor. He compares noble aims to

true north on a surveyor's compass. True north is essential, he tells Stevens,

but you also have to navigate "the swamps and deserts and chasms along the

way.” If you can't do that, he asks, "what's the good of knowing true

north?"

Trudging into 2013, I believe we’re pointed north. We’re

girded with the right values. Our challenge is to not be blinded or guided

completely by principle, though.

We’ll only successfully move forward if we acknowledge the muck and mire

that stands before us. If we

navigate the politics, the complicated feelings, the fact that our past does

remain with us, then we can successfully traverse the difficult issues –

hopefully reaching that most principled peace at journey’s end. Ken yehi ratzon.

No comments:

Post a Comment